Mister Brisbane: Electorate lottery

Who decides how our city and country are carved up into voting divisions?

People of my generation will be well aware of “Joh’s gerrymander” (or “Bjelkemander” as Wikipedia calls it), which gave a huge electoral advantage to Joh Bjelke-Petersen and his Country, later National, Party by allowing for rural seats to have far fewer voters than city-based ones. At its most blatant, the Brisbane electorate of Mount Gravatt had 26,307 voters, while the seat of Charters Towers in northern Queensland had just 4,367.

To be fair, the system pre-dated Joh and it wasn’t just his side of politics that historically benefitted from gerrymandering.

We now have a system in place to, more or less, ensure electorates are of a similar size so that one part of the population’s vote isn’t “worth more” than any other.

I started thinking about that because, in the lead-up to the Federal election on May 21, there’s been a lot of talk about certain politicians being at risk because of shifting demographics in their electorates.

My first, somewhat naive, response to this is that any politician who genuinely aspires to govern well for all Australians should not have to fear changing demographics in their electorate. They should have policies that appeal across the board. Of course, that’s not how it works, because politics can’t be “done right” for everyone. Our situation in life, and our values, affect how we vote, and some of us stubbornly vote for the one side for all our lives, whether that’s in our best interests or not.

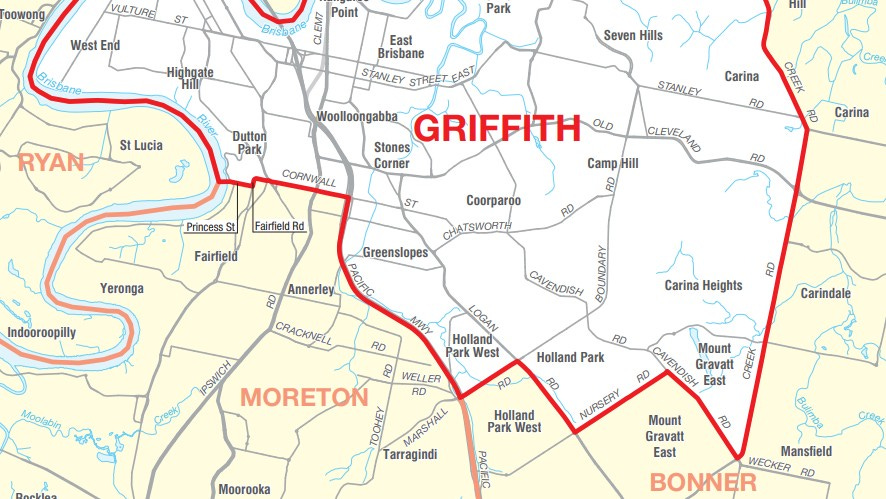

I’ve already voted in the federal election, because I’m going to be working on polling day. This is the first time I’ve had to vote at my current address, which is very near the border of the Griffith electorate. Many voters who share my postcode are in Bonner. The dividing line is the otherwise unremarkable Creek Road.

What makes people living on one side of that road different to those on the other? Not a lot, I would say. But, at the time of writing, Bonner has a representative who is a member of the Liberal National Party, while Griffith is held by the Labor Party. There is no doubt that there are Labor voters in Bonner and Liberal voters in Griffith, along with people who support neither of the major parties. So, are their interests fairly represented?

When we buy or rent a property, do any of us consider which electorate we’ll be in? has anyone ever said, for example, “Oh, no, Dickson is a deal breaker.”

My point is that, while a lot of science goes into drawing up state and federal electorates, there is still an element of arbitrariness to the process. Those electorates do not always represent communities of interest (do the people of Murarrie have a lot of affinity with those of West End?), and even if they did, well, those things change over time.

As it is, there are people who will never have a local member who represents their own personal brand of politics. On the macro scale, the system means there will be occasions when more individual Australians voted for members of the party that is in opposition than for the one that is in government.

Are there better answers, such as larger, multi-member electorates?

Is it a stretch to say that, especially in tight elections, the real power in Australia is held by those who draw up the boundaries? Or, indeed, that the system of geographic constituencies is inherently undemocratic?

FEEDBACK

I received a lot more responses identifying my recent discovery that what I’ve called a jam and cream doughnut all my life is better know in some circles as a “Long John”. My go-to explanation that, like potato scallop, it’s a Queensland thing , was shattered when a friend of similar vintage to me, who was born and bred in these parts, reckons he’s always called it a Long John.